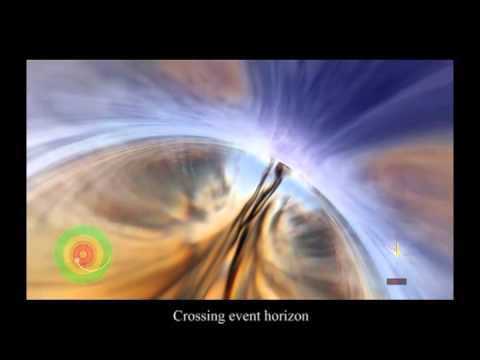

In many ways, a wormhole resembles a black hole. Related: Weirdly-shaped wormholes might work better than spherical ones No one knows if such exotic matter actually exists. The only way to keep them open and traversable is with an exotic form of matter with so-called "negative mass." Such exotic matter has bizarre properties, including flying away from a standard gravitational field instead of falling toward it like normal matter. In principle, all wormholes are unstable, closing the instant they open. Einstein's theory of general relativity allows for the possibility of wormholes, although whether they really exist is another matter.

From there, we can do more to understand the dust that surrounds them, and find out how many are hidden in distant galaxies.Wormholes are tunnels in spacetime that, in theory, can allow travel anywhere in space and time, or even into another universe. JWST will be far better at finding them, therefore we will have many more to study, including ones that are the most difficult to find. With JWST we are expecting to find many more of these hidden growing black holes. He adds, "The difficulty in finding these black holes and in establishing precise distance measurements explains why this result has previously been challenging to pin down these distant 'cosmic noon' galaxies. But these same black holes can be found using infrared light, which is produced by the hot dust surrounding them." Chris Harrison, co-author of the study, "These supermassive black holes are very challenging to find because the X-ray light, which astronomers have typically used to find these growing black holes, is blocked, and not detected by our telescopes. Sean Dougherty, postgraduate student at Newcastle University and lead author of the paper, says, "Our novel approach looks at hundreds of thousands of distant galaxies with a statistical approach and asks how likely any two galaxies are to be close together and so likely to be on a collision course."ĭr. It applies a statistical approach to determine galaxy distances using images at different wavelengths and removes the need for spectroscopic distance measurements for individual galaxies.ĭata arriving from the James Webb Space Telescope over the coming years is expected to revolutionize studies in the infrared and reveal even more secrets about how these dusty black holes grow. This study presents a new statistical method to overcome the previous limitations of measuring accurate distances of galaxies and supermassive black holes at cosmic noon. This makes it very difficult to know with high precision if any two galaxies are very close to each other. Understanding how black holes grew during this time is fundamental in modern day galactic research, especially as it may give us an insight into the supermassive black hole situated inside the Milky Way, and how our galaxy evolved over time.Īs they are so far away, only a small number of cosmic noon galaxies meet the required criteria to get precise measurements of their distances. They applied this new method to hundreds of thousands of galaxies in the distant universe (looking at galaxies formed 2 to 6 billion years after the Big Bang) in an attempt to better understand the so-called 'cosmic noon', a time when most of the Universe's galaxy and black hole growth is expected to have taken place. The researchers developed a new technique to determine how likely it is that two galaxies are very close together and are expected to collide in the future. The team made use of data from many different telescopes, including the Hubble Space Telescope and infrared Spitzer Space Telescope. However, the astronomers conducting this study were only able to detect the growing black holes using infrared light. This energy is typically detected using visible light or X-rays. In the final stages of its journey into a black hole, gas lights up and produces a huge amount of energy. One possibility is that when galaxies are close enough together, they are likely to be gravitationally pulled towards each other and 'merge' into one larger galaxy. However, what drives the gas close enough to the black holes for this to happen is an ongoing mystery.

These black holes grow by 'eating' gas that falls on to them. They have masses equivalent to millions, or even billions, times that of our Sun. Galaxies, including our own Milky Way, contain supermassive black holes at their centers.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)